Hometown, NZ.

It’s a tall order for any small town to attempt to fill, but along an unassuming road just over a hundred kilometers north of Wellington, a little place called Foxton, population 2,700, dares to make such a claim.

Maybe it was an instinctive desire to prove it wrong or just the obscurity of the attractions it offered – from a river cruise to a Dutch windmill, from museums devoted to such items as trolley buses, flax strippers, and dolls to New Zealand’s only clydesdale-drawn tram (presumably there to transport visitors from museum to museum) – but something drew me in, forcing me to turn off the state highway and venture closer to the town’s main street area.

Over the roof of a building whose art deco facade read “Municipal Chambers 1923” in burgundy and blue, the sails of a 17th-century style Dutch windmill turned slowly, deliberately. Three people gathered under the shade of a red domed awning hanging over the entrance to the building, whose municipal function has since been transformed into the town’s information center. I took a step back to the other side of Main Street, trying to capture the days-gone-by architecture of the Chambers and the unusual presence of such a windmill in a single shot.

It’d been a while since such latticed sails had floated across the frame of my camera and I was transported instantly to a visit two years earlier to Zaanse Schans, an open air heritage museum just outside of Amsterdam. There, friends and I had wandered along the banks of the Zaan River, stopping at each of the thirteen, centuries-old windmills, and taking pictures of each other standing in gimmicky, oversized clogs.

But today, instead, I found myself oceans away in Foxton, New Zealand, and I felt at once the sense of displacement that comes when any symbolic structure – be it the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, or a Dutch windmill – is removed from the place of its origins and replicated in a markedly different locale. For these structures carry with them certain associations linked specifically with their original homes. La Tour Eiffel is Paris, it is tied inextricably to the romance and wonder that is all things French, and I can only imagine the disjointed feeling of stumbling across its likeness in Las Vegas.

So, too, inside Foxton’s De Molen windmill – literally “the mill” in Dutch – I scratched my head and found myself asking, “Huh?” Rows of colorful magnets on a refrigerator spelled HOLLAND and were made in the shape of Amsterdam’s famous row houses or bunches of red and pink tulips stuffed into yellow clogs. I could’ve bought any number of Dutch delicacies on sale or sent a postcard as if from the Low Countries themselves, with only the postmark to betray me.

While I contemplated bottles of Maggi sauce and pancake mix, an aged volunteer running the gift shop explained that this is no mere tourist showpiece, but a working windmill since its grand opening in 2003. As if to prove his point, he motioned to a series of shelves displaying brown paper packages that contain the mill’s very own stone ground maizemeal.

I picked up a bright orange brochure that featured the outline of a tulip next to a silver fern – “Samen staan we sterk!” it read, “Let’s create a stronger community of Dutch Kiwis throughout New Zealand.” Having a friend from Christchurch currently living in London on a Dutch passport courtesy of his father’s lineage – with even the standard “van” prefix to prove it – I didn’t laugh off the endeavor as quickly as I might’ve otherwise.

There’s a lot of emphasis placed on Asian-Pacific groups now settled in New Zealand – Samoan, Fijian, Tongan, etc – but Kiwis of European descent are often lumped together under the umbrella term of pakeha, a Maori word that generally means white or non-Maori. So to learn of an individual European culture earnestly asking such questions as “Who are we?” and “Are we relevant?” was quite the unusual discovery.

I left Foxton perplexed yet thoroughly pleased that such an outpost of Dutchness exists and soon continued through the Manawatu District, where the motto is “Young Heart, Easy Living,” and a town named Sanson tempts passer-bys with its “Amazing Maze ‘n Maize.” Barely half an hour down the road, I passed quietly into Bulls, population 1,750. A black sign reading “Welcome to Bulls” featured a large white cut-out of a bull but did little to entice me off the road. New Zealand is full of towns with giant kiwis, giant sheep, and giant carrots, and as Joe Bennett writes in A Land of Two Halves, the humor behind these oversized landmarks is questionable:

“It’s a form of branding for the tourists, one that I would like to believe was tinged with irony, but I am not confident.”

But a life-size bull parading as a Dutchman does catch my attention. Painted on the side of a Dutch deli, he stands upright, sporting a blue peacoat and black pants, a red scarf tied around his neck, and of course, the unmistakable yellow clogs. He’s placed in front of that old familiar windmill and a trail of hearts drifts away from his head as if leading to a thought bubble, no doubt a result of the permanent position from which he gazes longingly at the saucy little heifer in a mural on the opposing wall.

I turned left at the next stoplight and parked along a side road. As I got out of the car, I was delighted to find an official rubbish bin shaped like an old-fashioned milk can. What’s more, the town’s logo had been painted on the side of the can with the words, Respons-I-Bull, printed underneath. I laughed to myself and congratulated the town on such a display of cleverness.

But it didn’t end there. I looked up to find the public restrooms directly in front of me. Obviously, not something incredibly noteworthy, except when a small white sign posted near the building read: Reliev-A-Bull.

It was like breaking a code, finding the legend to a treasure map, or the moment when after staring cross-eyed at an autostereogram, the hidden image finally pops out at you.

I knew not only how to look, but where, and soon spotted white sign after white sign, all filled with their shamelessly entertaining puns. Outside the New Zealand Fire Service of Bulls? Extinguish-A-Bull. The Bulls C.A.L.F. Playschool, short for Childcare and Learning Facility? Love-A-Bull. The Plunket Society, an organization that provides health services to babies and young children? Non-Return-A-Bull. It may not have been the finest display of verbal irony, but I ate it up nonetheless.

I walked back towards Main Street, passing by the Dairy Bull, where apparently a range of products is Avail-A-Bull, and came to a sports bar named, for whatever reason, the Rat Hole. There was no sign to be seen at first, so getting into the spirit of things, I thought “Drink-A-Bull” or even “Imbibe-A-Bull” might do. A second-hand bookstore was named Trash and Treasur-A-Bull, prices at the electronics store were Unbeat-A-Bull, and the Candy Cottage absolutely Irresist-A-Bull.

I browsed further through town, picking up momentum like you might in an Easter egg hunt after finding that one egg with paper money inside. A sign on the ATM at Westpac Bank read Bank-A-Bull and the Bulls Museum, with all its antique sewing machines and phonographs, was sure to be Memor-A-Bull. Although I found several establishments lacking in creativity – Mr. Sharp Sharpening Services could have certainly done better than Sharpen-A-Bull – many were quite original, with even the Anglican church taking part in the fun: Forgive-A-Bull.

After close to an hour of sign-chasing, from the Indispense-A-Bull Platt’s Pharmacy to the Cure-A-Bull medical center, from the List-A-Bull real estate agency to the Restock-A-Bull 4Square Market, I turned to the information center – Inform-A-Bull, of course – to help me trace the history of such an inimitable marketing campaign.

Inside, a man named Roger tells me the town itself wasn’t even named after its four-legged counterpart but James Bull, an English carpenter whose first job in New Zealand was to build a chair for the Parliamentary Speaker in Wellington. Roger calls on a coworker to remember exactly when the signs first appeared, sometime in 1991 it seems, and they were based off a book called A Load of Bull, naturally. To date, there are well over a hundred signs and ten alone have appeared in the last six months. All it took to get started was the support of local businesses…easily Achieve-A-Bull, no?

Bulls, a self-proclaimed “town like no udder,” proved truly “unforgettabull,” just like the brochures and websites profess. Even on the road leading out of the town, there was a banner to see me off:

“Bulls – Where anything is poss-a-bull.”

I can describe my departure from Bulls as nothing short of regrett-a-bull, but there was still plenty of road left between me and where I planned to be by the end of the day.

Much of the traffic that passes through Bulls comes from the fact that the town is located at the fork of two state highways. SH1, the route I’d taken from Wellington, continues north through the center of the island, but I “steer”ed left (pun fully intended), following SH3 towards Wanganui and Hawera, where I’d continue on SH45 to New Plymouth. The region I was entering is home to Mount Taranaki and a sign, “Welcome to the Horizons Region,” marks your arrival. I liked the sound of that.

I approached Hawera rather indifferently. With a population of 11,000, the town seems to be known for little more than having the largest dairy factory complex in the Southern Hemisphere as well as an iconic water tower built in 1914. As I pulled up to the tower, though, my attention was diverted to a series of American flags hanging from the light poles that lined the streets. It was more what I would have expected to find in small-town America on Memorial Day or Fourth of July, not here of all places. I found the information center and walked up to an attendant, asking vaguely, “Any reason all those American flags are hung?”

“Oh, yes,” she replied quickly, “AmeriCARna.”

Why hadn’t I thought of that? Of course the arrival of 700 antique American cars over the weekend explained such a display of patriotism…for a country not their own.

In Manaia, I was greeted by a giant loaf of bread, in honor of the town’s self-avowed status as “The Bread Capital of New Zealand.” There was a charming roundabout in the center of town, with a clocktower, gazebo and war memorial, as well as the Taranaki Country Music Hall of Fame.

Yet it is bread, not banjos, that seems to be key to this township’s success. The Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand describes Manaia as the “hub of a thriving baking industry” and a brochure on historic Manaia lists the Yarrows Limited’s factory as the country’s largest privately-owned bakery. When a flour mill was first built in 1882, it was even thought “Taranaki would become the grain growing area of the South Pacific,” yet the mill’s remains today might suggest otherwise.

I began to wonder if I would ever make it to New Plymouth. The trouble with the open road, open not only in space but in the sense that it is yours for the taking, is when do you stop stopping? Driving solo is the pinnacle of independence, with not even a fellow passenger to insist, not another small town…enough already!

I had a feeling all my calculations of driving times and estimated arrival times to destinations would swiftly grow irrelevant as the North Island unveiled the best it had to offer in both the quirky and quaint.

But something I have come to love about New Zealand while driving around it is the character and personality so many of its highways take on. Because of its relatively small size – its land area roughly the same as the United Kingdom’s and just 3% of the United States’ – the highways in New Zealand are fairly straightforward. No messy exits, no confusing clovers, just one road in, one road out. And for sections of the highway designated as official touring routes, they are marketed as such: the Great Alpine Highway on the South Island, the Twin Coast Discovery Highway leading from Auckland to the top of the North Island, and – what I would be taking from Hawera to New Plymouth – the Surf Highway, otherwise known as State Highway 45, that wraps around the coast circling Mount Taranaki in a shaky half-moon.

Opunake, a little town of 1,300 and “Home of World Famous Surf,” lay along the Surf Highway. In town there was an Opunake Hotel and the Surf Inn, complete with a kayak hung on the roof, but I turned down a side road and headed towards the coast.

There was a small walkway I took that weaved through the bush and brought you out on a cliff overlooking the main beach, its black volcanic sand shimmering in low tide. A single vehicle had been parked at the water’s edge and two figures worked their way across the sand. I walked back to my car and drove down to sea-level, where a campground and holiday park had been built. Two hexagonal picnic tables were placed in front of the Opunake Beach Camp Store and a family sat on the grass in the waning sunlight. It was a sleepy sort of place, a thin layer of algae floating on the campground’s pool, but I had the feeling those who visit don’t mind.

The highway continued and I settled in for what I thought would be a final hour of driving before New Plymouth. That is, until, a hand-painted sign in a yard outside the town of Rahotu caught my eye and offered an invitation: “Welcome to view, wander around.” View what? I asked, taking in the picket fence that stood between the road and a small, plain house with white siding and a red, corrugated metal roof.

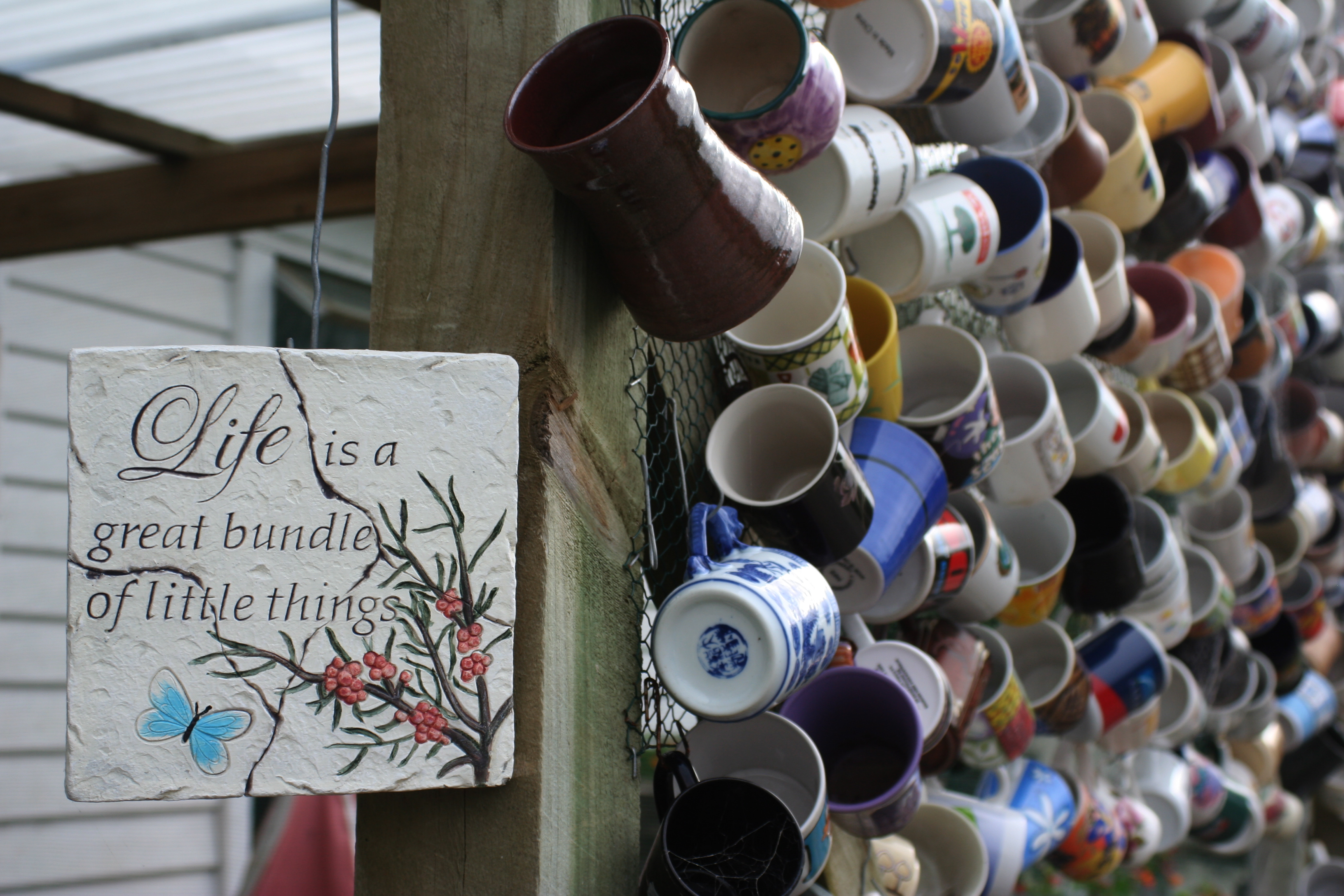

I walked closer and found that the two pieces of wood holding up the sign had hooks in them and from each one had been hung a coffee mug. There were easily twenty cups on either side. Additionally, the entire interior of the fence was covered with mugs, as was the base of a wishing well, the sides of a chest freezer, the mesh around a chicken coop, and even a retro mini RV standing in the yard.

On one side of the house hidden from the road, the same hand had painted “Krafty Cups” in large red lettering, right next to a wooden lattice holding more mugs. The cups were everywhere.

I crossed the yard cautiously, with that certain hesitance of trespassing yet intensely curious. What would behoove someone to do such a thing? For someone to go to the effort of not only collecting an obscene amount of coffee mugs, but to then take the time to string the wire and secure the hooks from which to hang each cup. And to what end? As some bizarre protest against conformity? A schoolteacher with nowhere else to store the mugs she’s given year after year? Or just a simple attempt to bring a smile to each passer-by and give them a story to take with them? “You’ll never believe what I saw…”

In the roughest of estimates, I figure there are thousands of mugs, hung with the greatest of care just like the stockings in The Night Before Christmas. It’s easy to think someone has way too much time on their hands…but then again, why not, right? I, for one, was grateful for whatever questionably-sound mind was behind it. It’s not the kind of place you can plan to visit, as it’s not exactly the kind of place you know even exists until you happen to chance upon it.

When I finally arrived at the Sunflower Lodge in New Plymouth nine and a half hours after leaving Wellington – still not sure exactly how a five-hour trip turned into that – I settled in in peace. In the kitchen, an old man who worked for the hostel was helping two young Dutch guys cook paua in a frying pan, a New Zealand standard that tastes similar to abalone (or so I’m told). They’d bought them off a guy on the side of the road and didn’t know how to open their shell, let alone cook them.

The man tells us that when he was our age, “You got straight to work. I got a job at 20, was married at 21, and by the time I was 25, I had four kids. I think what you guys are doing is a great way to get around.”

I got to know my Finnish dormmate briefly back in the room. A feeling of contentment washed over me – not the exhilaration of a crazy adventure, but that quiet satisfaction of knowing what I’m doing and knowing why I’m here. This day was exactly what I had hoped for and perfectly justified every cent I was spending on a rental car. I thought about the fact that this trip didn’t exactly have any edginess to it and it’s not as if I felt I was driving off into the great unknown, even if I had been referring to the North Island as my ‘terra incognita’ the past year. But it did feel like a journey of exploration. I thought of Captain Cook on voyages around the world, armed with painters ready to record the new sights, and I felt it was much the same for me and my camera.

The thing is, I expected quirkiness. So when I stumbled upon something out of the ordinary – be it a Dutch windmill, an oversized loaf of bread, or a cache of coffee cups – I laughed out of excitement, not surprise, as if to say, “Ah, so here’s where you’ve been hiding.” As I fell asleep that night, I couldn’t help but feel like the promise behind Taranaki’s “Horizons Region” was true…

I’ve recently read Kerouac’s “On the Road” and the descriptive narrative on this blog is possibly just as good.